The Ephemeral City

March 31, 2019

Last month, Stanford University invited me to be a part of its ArtsWest symposium, “Burning Man: Art and Technology.” Organized by the Bill Lane Center for the American West, the event was held at the de Young Museum in San Francisco on February 23, 2019.

It’s not the first academic symposium to explore the social and cultural significance of Burning Man, but it was certainly one of the more high-profile. Much of the recent scholarly attention reflects the fact that Burning Man has gone from a fringe event—one started by a handful of renegade artists and performers in San Francisco—to a worldwide cultural phenomenon.

In my talk, I presented some of my images from Burning Man and reflected on what I’ve learned from fifteen years of attending the event as a photographer, journalist and cultural observer.

What follows is the text of my talk—which was titled “The Ephemeral City”—along with a handful of the photos shown on the big screen.

I had no interest in going to Burning Man when I first heard about it in the mid-90s. I had seen photos of people doing wild and crazy things in the desert and I decided it wasn’t for me. If I ever make the trip to the Black Rock Desert, I thought, it will be to enjoy the solitude and wide open spaces, not to share the place with tens of thousands of other people.

But in the year 2000, my girlfriend went to Burning Man with some friends and came home insisting we go together the following year. I put up a lot of resistance to the idea. But evenually I came around and agreed to go—mostly as a favor to her.

We arrived at Burning Man that first year in a full-on whiteout, which only confirmed my sense that the trip was a complete mistake. After the winds died down and the dust settled a bit, we looked around and started taking it all in. It struck me almost immediately that Burning Man was nothing like what I expected. It was less of a festival in the traditional sense, and more of a creative experiment.

By the end of the week, it had dawned on me that there were fascinating stories to tell about what I was seeing—about art that is interactive, about the power of creative community design, about gifting and free exchange, and about “self-expression” and what it means to experiment with alternate personas and identities.

I felt that these ideas were worth documenting and sharing. But it wasn’t clear to me as a journalist how best to do that. I didn’t want to write a long feature article about my experiences at the event. For one thing, there were already a lot of articles like that in print—some of them written by brilliant writers and cultural icons like Kevin Kelly and Bruce Sterling.

Even if I were up to the task of writing a good piece, I wasn’t sure that words were the right medium for what I wanted to convey. Burning Man is a kaleidoscopic visual experience. Mark Morford, columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, once described it as “nonstop visual orgasmica.” I felt that words alone couldn’t do it justice. So I came up with the idea of doing a photo essay combining images and text. I wanted to have people describe the Burning Man experience in their own words.

The photo essay is a tried-and-true journalistic method, as we know. There was just one problem—I wasn’t much of a photographer. I was a writer and radio journalist. I had an early love affair with photography as a teenager and went on to study it in college, but then I put the camera aside and built a career around other pursuits.

After that initial visit to Burning Man, I returned the following year with a pair of decent cameras. I spent eight full days doing interviews, taking notes, and making pictures. At the end of that week—looking over the photos and the voluminous notes I’d taken—it was clear to me that the images stood on their own. They didn’t need any captions. Words seemed unnecessary. (It was a powerful moment for me as a journalist, and a very humbling one.) So from that moment forward, I concentrated on just making pictures.

It wasn’t lost on me that being a photographer at Burning Man violates the essential spirit of the event. Unlike a traditional festival where you go to be entertained in some way—where there is a clear boundary between the performer and the audience—Burning Man is entirely participant-driven. Everybody contributes something to the overall experience.

Susan Sontag, the late writer and great social critic, once said that “photography has become one of the principal devices for experiencing something, for giving an appearance of participation.” But, she said, “the camera makes everyone … a tourist.” If you’re taking pictures, you’re not participating fully in the moment. You can’t be immersed in what’s going on at the same time that you’re standing on the sidelines taking pictures.

Burning Man is notoriously difficult to describe, and no one seems to know quite what to call it. It’s referred to as a public art festival, as we know. It’s been called “a new American underground.” “A countercultural convergence. ” “A whimsical fairyland.” “A flea market Las Vegas.” “Disneyland in reverse.”

For me, the phrase that comes closest to describing it is “an experiment in temporary community.” This phrase captures the fact that it’s an experiment and that it’s ephemeral. It’s not a place you go to, in other words, it’s an experience you have—one that lasts a few days and then, when it’s over, what’s left are the memories. And hopefully a few good photos.

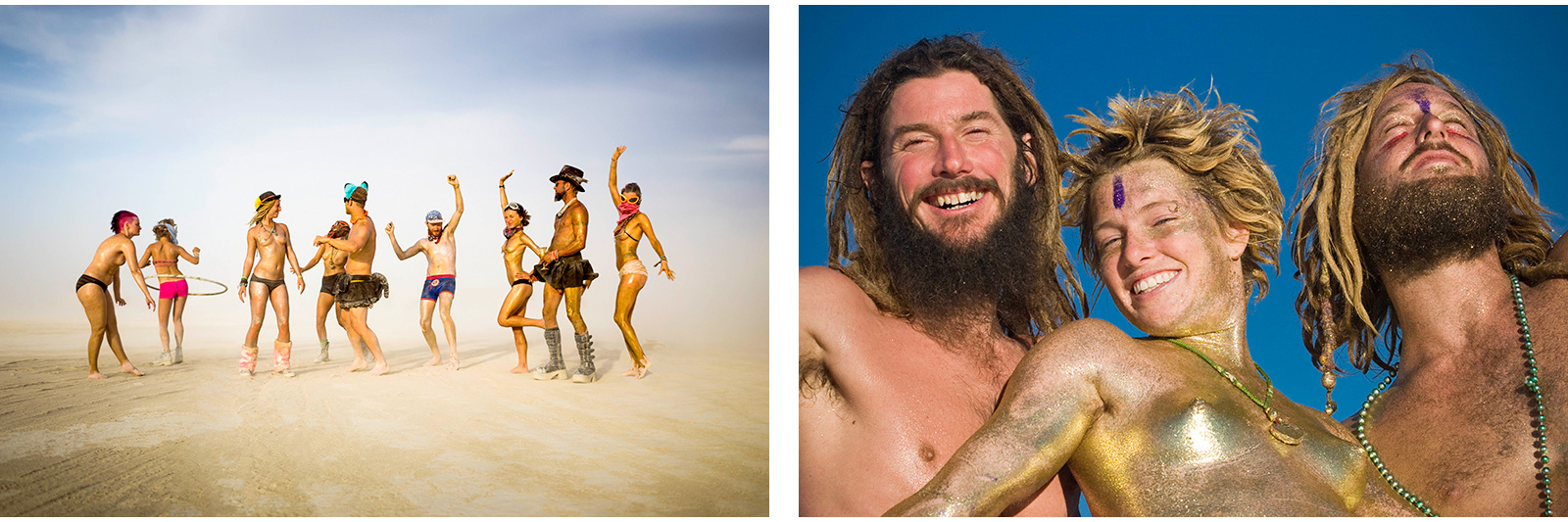

Unfortunately, the media have persisted in framing the event as nothing more than a bacchanalian orgy in the desert. The focus tends to be on the nudity, the drugs, the hedonism, the sheer excess of it all. A case in point: Time magazine called it “one of the most unbridled examples … of 21st century self-indulgence.”

But as a journalist, I saw a very different story playing out when I arrived at Burning Man. I felt that spinning it as a big desert rave missed the significance of the event as a kind of test-tube experiment. Let me mention just a few aspects of the event that struck me as fascinating and under-reported.

One of them, which I’ve already alluded to, is the idea that everyone is a participant. This idea may not seem very radical on the face of it, but look at how little time we spend actually doing that in our culture. Our recreational activities are almost entirely passive. What we do is spectate. We go to a ballgame and watch from the stands, or we sit on the couch and stare at the TV, or we scroll through our Instagram feed. In other words, we watch other people doing things, often looking in from the outside. So being an active participant represents an entirely different proposition. You don’t come to Burning Man to be entertained, you come to Burning Man to be the entertainment.

Another storyline is the power of creative place-making. At Burning Man, everybody is making stuff. Whether it’s a big theme camp, or a scrappy art car, or a beautiful temple, the whole place is like a giant Makers Faire, a haven for techies, gear-heads, and mad geniuses.

The act of building and creating something together is a powerful way to build bonds and create community. I know a number of Burners who come just for the build. By the time the gates open and everybody starts to arrive, they pack up and leave. They’re not there for the party—they are there for the barn-raising, for the chance to spend time with a crew of friends and build something together.

Another core aspect of Burning Man, one that I don’t think people pay sufficient attention to, is the fact that no money changes hands at the event. I realize that it takes money—sometimes a lot of it—to get yourself out to the desert. But once there, there are no vendors. You can go for a full week or more without having to pull out your wallet.

The gift economy is a very interesting aspect of Burning Man. When people give freely without any expectation of return, it creates a positive feedback loop. When we’re on the receiving end of an act of spontaneous generosity, we tend to pay that forward by being more generous to the next person we meet. This can have an immensely powerful impact on a group of people. (And needless to say, when people are selling stuff or marketing things at you, it tends to have exactly the opposite effect.)

This is Brother Baker and his “lovin’ oven,” as he calls it. He brought it all the way from Brooklyn so he could wheel it out to the temple each morning to bake croissants for people.

One hot afternoon back in 2006, a refrigerated truck pulled up on the playa, and a crew jumped out and started serving free ice cream. There was no branding on the truck or on the cones they were handing out, but I happened to recognize this man on the right. That’s Ben Cohen—co-founder of Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream.

Here’s another amusing example of gifting at its finest. These guys were offering to lube people’s bikes using bacon grease from back at camp.

Another storyline at Burning Man is the power of intentional community design. The ephemeral metropolis known as Black Rock City, with its population of about 70,000 people, is designed around open spaces, public art and people-friendly plazas. It’s designed for pedestrians and people on bikes rather than cars. It’s designed to maximize the number of spontaneous encounters between people.

There is a growing body of literature on the power of spontaneous exchanges and how they’re one of the keys to good urban planning. As an experiment, go to Burning Man and count the number of strangers you meet in a day, then compare that to the average number of strangers you meet on a typical weekday at home. I think the difference will amaze you.

I’ll come back to these different themes, or dimensions, of Burning Man. But let me say a few words about how this project of mine evolved. When I got back from Burning Man that second year, I felt that it wasn’t enough just to post a group of images online. I wanted them to say something. I had a sense that if I selected the images carefully and sequenced them just right, they might speak together as a series. I decided to post 100 of my best images from the event on my website. I called it a photo essay, but there was no actual text and no captions.

I did put a fair amount of intention into all of this. But still, it was a modest little project. To my surprise, the photographs found an audience almost immediately. Some of the visitors to my site were people who had been to the event and who were looking to re-experience it through photos. I think this is quite common for people to do after they get back from the event. But it seemed to me that the majority of visitors really had little or no prior knowledge of Burning Man.

Bear in mind that it was the early 2000s, and the world wasn’t yet overrun by Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Not every photographer had his or her own website. There were plenty of photographers at Burning Man, but very few who posted images of the event online after it was over. I might have been the only one who created an actual photo essay.

As more and more people discovered the images, photo editors for newspapers and magazines started getting in touch asking to publish the images. A 9-page spread in Nevada magazine actually won a prestigious magazine award. This was just a year or so into the project.

This photo, which I call “Blue Lovers,” was made in 2009. It was featured on the cover of Common Ground magazine.

In 2011, Ev Williams, the co-founder of Twitter, saw my photos from that year and shared the link with more than one million of his followers. That was an important milestone. The photos went viral and soon I had so much traffic to my site that I couldn’t keep up with all the e-mail and comments. In one week, I had over one million unique visitors to my site.

All of this exposure allowed the images to be seen by new audiences, people I’d never reached before—book editors, gallery owners, museum curators, TV producers, even corporate ad people looking to license cool photos. (That, by the way, is not something the Burning Man organization allows. All of us professional photographers have to sign a contract to that effect before we shoot at the event.)

The photos also started to appear in more and more magazines. In 2012, Rolling Stone magazine invited me to cover Burning Man on assignment—something I did for four years.

In 2014, I put out a coffee-table book: Burning Man: Art on Fire with writer Jennifer Raiser and fellow photographer Sidney Erthal. The book actually became an Amazon bestseller in several categories, which amazed all of us, and it also got a good deal of attention in the media. We published a second, expanded edition in 2016.

I mention all of this exposure because it became clear to me at a certain point that Burning Man had become something of a phenomenon—a kind of cultural touchstone. References to the event were now cropping up in song lyrics, on The Simpsons, and in speeches by President Obama.

Yet this was the thing: the old media narratives didn’t go away. There was still a general sense on the part of the news establishment that Burning Man was just a big hippie rave in the desert.

Other story angles kept showing up in the media as well. Headlines would make the case that Burning Man had “sold out,” that it was going “mainstream,” that it was somehow “played out.” Or that it was becoming too commercialized. This, of course, is complete nonsense. How can an event where nothing is for sale be too commercial?

I knew better than to think I alone could change anybody’s perceptions. But what I could do, perhaps, was try to be very intentional about what I was doing and use a wider-angle lens, so to speak—to offer a more expanded perspective of the event.

I’ll go back to the moment an editor from Rolling Stone contacted me in 2012. That may sound like a dream assignment. But I was actually a bit reluctant to shoot for the magazine. A friend of mine, a fellow Burning Man photographer, had covered the event for Rolling Stone in the early 2000s. He had worked very hard out there and used up a lot of social capital making images that were difficult to get. After he submitted his images, he found that the magazine’s editors had paired them with a short write-up, cobbled together by some in-house writer in New York, that was deeply critical of the event. All of his hard work was being used in service of a snarky article about a “freakshow in the desert,” or something to that effect. He was devastated by this, and some of his friends at Burning Man felt that the coverage was a kind of betrayal.

So when I got the call from Rolling Stone, I said that I’d only be willing to shoot for the magazine if they gave me their assurance that the coverage would be fair and even-handed. Well, they couldn’t promise that. So I said, how about if I write the captions? The editor thought about it and we came to an agreement: they would craft the headline and the lede, and I could write the captions for the photos. … This is what they came up with:

Working for Rolling Stone was a creative challenge for me. It forced me to think very carefully about what I was doing at Burning Man. For one thing, I realized that most of the readers of Rolling Stone had never been to the event—they had only heard about it from friends or seen references to it online or in the media.

For this reason, I tried to avoid some of the more hackneyed themes, and always ask myself: what am I trying to communicate here? What’s the story here? I became a lot more focused on what I saw as the essence of Burning Man and why it’s significant. It made the gig a lot harder, but also a lot more rewarding from a creative standpoint.

Let me say just a few things about what, for me, is at the heart of the Burning Man experience.

A favorite book of mine is called The Act of Creation. It was written by the British novelist and writer Arthur Koestler. He devoted years of study to creativity in science and the arts—and actually did some excellent work here at Stanford in the mid-60s. Koestler observed that our minds are constrained to think within limited contexts or frames of reference. And creativity, as he described it, was the coming together of two seemingly unrelated frames of reference.

According to Koestler, the creative act plays out differently in comedy, in science, and in the arts. In comedy, it takes the form of a collision: you’re following the story along and then comes the punchline and you suddenly realize you’re not in the context you thought you were. In science, the creative act takes the form of a synthesis. In the arts, it takes the form of a juxtaposition. Koestler had a clever way of describing the effect of this process. In comedy, he said, the reaction it produces is ha ha. In science, the reaction is aha! In art, the reaction is aaah…

You can see these reactions everywhere you turn at Burning Man, because the event is all about juxtaposing incompatible frames of reference. The whole thing is a kind of theater of the absurd. A sixteenth-century Spanish galleon gliding across the desert floor. A group of bankers in dusty painters’ overalls holding umbrellas and briefcases. An old country church tipped on its axis, like a mouse-trap.

It’s like walking around in a Salvador Dali painting. In fact, like so much of the art and writing from the surrealist period, what you experience at Burning Man can be startling, unconventional, hilarious, mystifying, and also, in some deep sense, eye-opening.

A lot of what you see at the event speaks to the power within all of us to create. We come into the world as immensely creative beings. Just look at the creativity of little children. But that creativity tends to be bred out of us. So, when as adults we arrive at a place like Burning Man that actively encourages us to participate, to create, to make and to share, we become awakened to something that lies dormant deep within us.

At Burning Man, the creativity is mind-boggling. There are the art installations. But there are also fire-breathing rhinos, bizarre allegorical performance pieces, marauding bananas, drinking chess, and burning pianos flying through the air.

Burning Man makes artists of us all. My own work certainly attests to that fact, but so does that of countless others at Burning Man—many of whom arrive at the event, bewildered and perhaps reluctant to be there, as I was, only to awaken some new capacity or artistic vision.

Another aspect of creativity is being freed from restrictive ways of thinking. Burning Man creates a context that sets people free to experiment with new modes of being. It frees us from social conventions. We can let go of old identities—or perhaps adopt new ones.

Most of us, especially here in America, like to think we’re free because we live in a more or less free society. But we’re trapped by our mental ideas and constructs. We live in a kind of bondage to habitual ways of thinking and perceiving the world. We live within carefully constructed identity bubbles that don’t leave much room for new growth.

So, there is something about going off the grid for a week and releasing ourselves from the confines of our everyday reality that can shatter that sense of limitation and “break open the head,” as Daniel Pinchbeck puts it. At Burning Man, you see this process playing out in a thousand different ways. For some people, it could mean adopting a special playa name, or assuming a different persona for each day of the week—each with its own name and set of outfits. For others, it could mean pushing the boundaries of their sexual orientation or venturing out far beyond their comfort zone.

How we choose to break free of our thought-prisons is a very personal thing, but the fact is that we need safe contexts in which to do it. There are very few public places in our society where that’s even allowed, let alone encouraged.

I think that for some people there’s freedom simply in being nobody in particular. I’ve struck up some of the most remarkable conversations with strangers at Burning Man, only to learn—deep into a long, heartfelt conversation—that they were wealthy entrepreneurs, prominent architects, Bollywood movie stars, nuclear physicists, sex workers, professors at elite colleges and universities. One time I had an hour-long conversation with with someone I later learned was the crown-prince [and now king] of a country in Europe.

One of the core principles of Burning Man is the idea of radical self-expression. Some people take that to mean defying convention in some way, like dressing up in a wacky outfit, or doing something daring in public. But after you’ve run around in the desert wearing nothing but bunny ears and a tutu for a few days, the thrill wears off. At that point you have to reach within yourself to find some experience, some capacity, some creative spark that connects with what makes you feel alive inside. To discover that and bring it forth takes courage. I think that’s what Burning Man’s founder, Larry Harvey, was referring to when he spoke of radical self-expression.

We need places in our culture where we can discover those capacities, where we can free ourselves from the shackles of our social and professional roles. I think many of us get this at an intellectual level. But the fact that there is a place where we can discover this at an experiential level is a different thing altogether. On the playa, it’s not an abstract notion, it’s a visceral experience.

Burning Man represents a kind of skunk works, a laboratory of creative possibility. I think we’re already seeing how some of the design characteristics that go into the event are beginning to inform and inspire changes in society at large.

This is reflected in much of the new thinking about public art and its role in building vibrant communities, for example. It’s reflected in some of the principles of innovative urban design. You see it in the ways more and more groups and organizations are emphasizing ritual and play as an integral part of everyday life. And you find it in the growing debate around commercialization and the need to curb its effects in everyday life.

These ideas are now shaking things up on a wide range of fronts. Burning Man, far from being something on the cultural fringe, now looks more and more like an expression of the cultural frontier.

Thank you very much.